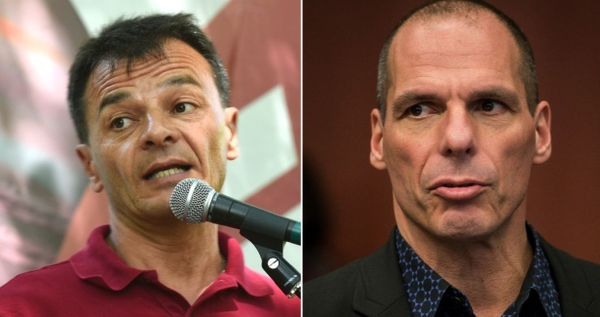

Stefano Fassina points out that in my article ‘Europe’s Left After Brexit’ I did not discuss his preferred option for Eurozone member-states: Stay in the EU but leave the euro. Of course the reason my article did not discuss that position is that it was focusing on Brexit and addressing Lexiteers like Tariq Ali and Stathis Kouvelakis who are arguing, from a left-wing position, for leaving the EU altogether – i.e. Brexit-like moves. But I am more than happy to comment on Stefano’s preferred option (In the EU, Out of the Euro).

An ‘amicable divorce’ for the Eurozone?

Stefano invokes Joe Stiglitz who, in his recent book on the euro, recommends an ‘amicable divorce’ that would lead to the creation of at least two new currencies (one for the deficit and one for the surplus countries). Since I have recently discussed this with Joe Stiglitz it is perhaps useful to share the gist of our discussion with Stefano and our readers.

In my email to Joe, I expressed scepticism that an ‘amicable divorce’ is at all possible. The moment it becomes public that a ‘divorce’ is under discussion, a wall of money will leave the banks of the countries destined for devaluation, heading for Frankfurt. At that point, the banks of the deficit member-states will collapse (as they run out of ECB-acceptable collateral) and the member-states will impose stringent currency and capital controls – complete with officials at airports checking suitcases and/or harsh limits in cash withdrawals. This would spell the end not only of monetary union but also of (the already injured) Schengen Treaty.

Meanwhile, as bank deposits are being redenominated, huge assets belonging to the Bundesbank and the central banks of other surplus countries (e.g. the Netherlands), which are the liabilities of the deficit countries, will disappear, causing an uproar of indignation in Germany and the Netherlands. Under such circumstances, and given the already advanced stage of the EU’s disintegration, it is almost certain that the dissolution of the Eurozone will be anything but amicable.

Joe Stiglitz responded to me thus: “You are absolutely right that the moment any country contemplated leaving, capital controls would have to be imposed… The rush out will occur presumably before–when a party advocating a referendum looks like it might win. So the hard decisions about imposing capital controls are likely to be faced ironically by a pro-Euro government. If it delays, by the time the election occurs, the country may be in shambles. The picture ahead for Europe is not a pretty one.”

In conclusion, it is a fantasy to think that the EU can oversee an amicable disintegration of the Eurozone. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the EU surviving a Eurozone breakdown.

Is DiEM25’s strategy of Constructive Disobedience a mere bluff for a Eurozone country?

Stefano Fassina writes: “While the strategy of “wilful disobedience”… can be effective in an EU country still controlling its currency and its national central bank, it’s unfortunately a bluff for a euro zone country under severe economic, social and financial stress, as the Greek case made dramatically clear.”

What the crushing of the Athens Spring made clear was not that I had been bluffing. It demonstrates simply that the defeat of a stressed government is inescapable if it is divided. Speaking as the finance minister of that period, I can assure the reader, and Stefano, that I was not bluffing. A bluff means that you are pretending to have a card, or preferences, that you lack – or that you will do something which you do not intend to do. When I was saying that I was not willing to sign the 3rd ‘Bailout’ Agreement, I meant every word. Why? Because I had ranked potential outcomes in the following order: (1) A viable agreement with the troika; (2) Being expelled from the Eurozone; (3) Signing the 3rd ‘Bailout’ Agreement. While option 1 was by far the preferred one, and Grexit was hugely costly both for Greece and for rest of Europe, the 3rd ‘Bailout’ Agreement was the worst outcome possible for everyone. In short, no bluff was involved when I proclaimed that I would not sign any agreement not based on (i) substantial debt relief, (ii) a primary surplus target of no more than 1.5%, and (iii) deep reforms that tackled the oligarchs (instead of the weakest of the citizens).

If my government had been united in this, our original, assessment, we would not have backed down and, as a result, either the troika would have relented or we would have had to create our own euro-denominated liquidity (that would, naturally, have an exchange rate with paper euros – as is, in fact the case today, under the ECB-imposed capital controls). At that point, Brussels-Frankfurt-Berlin would have had to make their choice: Step back from the brink or push us out of the euro by violating many of the EU’s own rules. I have little doubt that they would have opted for the former (as Grexit would have cost the Eurozone around a trillion euros). But I would have remained unperturbed if they did not.

Stefano asks correctly: “What national government could negotiate relevant violations of the rules without a workable alternative on the table?” This is why, well before I took office, I had begun working on two plans: First, a Deterrence Plan by which to give pause to the ECB before it shut our banks down. Secondly, a Plan X to be activated when and if the troika chose to expel us from the Eurozone. However, it must be said that the idea that these plans could become operational before the rupture is just as much of a fantasy as that of an amicable disintegration of the Eurozone – see above. Put simply, any attempt to make these plans operational would trigger instant exit from the Eurozone – an exit that would happen well before they had become operational. Which means that the short-term cost of a rupture is bound to be large. Nevertheless, this was a cost that the majority of the people of Greece had instructed us to disregard in the pursuit of emancipation from debt bondage.

False consciousness

Stefano has a good point when reminding us that the euro is not simply the darling of large business but has broad support from many quarters: German trades unions that have been co-opted in the country’s mercantilist model, well meaning middle class people from both North and South etc. This is so, for reasons that I have laid down in my recent book “And the Weak Suffer What They Must?” But this is, it seems to me, an excellent reason to avoid turning the disintegration of the Eurozone into our objective (given that an ‘amicable divorce’ is an impossibility – and Europeans understand it to be so) and, rather, set our sights on a strategy of proposing sensible policies which convince even those who remain loyal to the idea of the euro that they are a good idea. Then, if the troika decides in its usual authoritarian and violent manner to threaten the democratically elected government with bank closures and liquidity squeezes, then even those who were in favour of the euro will come out on the streets to defend their government. Is this not what happened in Greece on the 5th of July 2015?

Conclusion

Stefano Fassina concludes by calling for unity amongst Europe’s progressives: “My point is to join forces,” he wrote. This is DiEM25’s raison d’ être – joining forces from across national borders and political party lines.

Like Stefano I too think that the Eurozone is disintegrating, probably in a manner that will also bring about the EU’s effective demise. However, my difference with Stefano is that I see no reason why we must adopt the Eurozone’s disintegration as our objective. Indeed, I see such an adoption as a major political error. Our joint task, as DiEM25 suggests, is to design a Progressive Agenda for Europe, one that points to:

• At the national level, progressive national governments offering their people a comprehensive Plan A – a glimpse of how, under the current system, hope can return to their country. At the same time, in Eurozone countries, they must have a Deterrence Plan in place for when the ECB and the troika respond to the progressive government’s Plan A with threats of bank closures, liquidity squeezes etc. And, lastly, they must have a third plan (Plan X, I called it) for when/if the ‘centre’ engineers their expulsion from the Eurozone.

• At the pan-Europen level, we need to offer Europeans a Plan A for Europe or a European New Deal as DiEM25 calls it – a glimpse of how, in a few weeks, under the current Treaties, hope, development and democracy could make a comeback across Europe. This Plan A must include a blueprint for managing (as well and as smoothly as it is possible) the painful disintegration of the Eurozone and of the EU.

To this end, a DiEM25 committee of experts has already begun work to produce comprehensive policies both at the national and the pan-European levels. At the same time DiEM25’s members will conduct similar work at the grassroots level. The issues covered include currencies, the banking system, public debt, investment and fighting poverty. The remit is to produce a European New Deal Policy Framework to be tabled by the beginning of February 2017 so that it can be debated, in a special two-day event, in Paris on the last week of that month, just before the French Presidential election campaign commences officially.

There is little time to lose. Europe is disintegrating without a plan either to stem its disintegration or to manage it. DiEM25 invites all European progressives to join in the massive undertaking of developing this plan – the European New Deal Policy Framework within the context of a broader Progressive Agenda for Europe.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here