Doubts that our world is morally indefensible become unforgiveable when even the bankers of the ultra-rich, along with the bailiffs working diligently on their behalf, are panicking about excessive inequality.

UBS recently reported that, between April and July 2020, as the pandemic’s first wave was surging, the collective stash of the world’s billionaires grew by 28 per cent and many millionaires joined their ranks. Surely the Swiss megabank is happy to see them laughing all the way to its doors, but it is also genuinely worried.

Similarly, the International Monetary Fund, an institution which for decades operated as the global oligarchy’s bailiffs, forcing governments — including one I served in as finance minister — to pursue inequality-boosting policies including privatisation of basic services, while eliminating benefits for the dirt poor, taxes on the wealthy etcetera. The extent to which the IMF has changed its tune amounts to an Ovidian transformation.

Even before COVID-19 subdued economies and drove the weak to hopelessness, the IMF was advocating raising income taxes on the wealthy. Now, in its October 2020 World Economic Outlook report, the Washington-based institution goes further, calling for progressive taxation, capital gains, wealth and digital taxes as well as a crackdown on the tax “minimisation” schemes by multinationals.

It is not, of course, concern for the billions of people driven into despair that has energised the likes of the IMF and UBS to call for action against breathtaking inequality. Their worry is that so much wealth has been siphoned off by the rich that the spending power remaining in the hands of the many is too feeble to keep demand up and capitalism in reasonable health. Like a lethal virus that rapidly killed off its host, and thus driving itself into extinction, capitalism is undermining itself by impoverishing and disempowering the “little” people.

To see how capitalism steadily undercut itself, it helps to begin in 2008.

Following the chain reaction that began with the collapse of US investment bank Lehman Brothers in the midst of the global financial crisis, central banks around the world produced mountain ranges of dirt-cheap debt-money to refloat the financial sector. At the same time, the vast majority of the West’s population was treated to universal fiscal austerity, which limited the ability for lower and middle income earners to spend. Unable to profit from austerity-hit consumers, corporations and financiers stayed hooked up to the central banks’ constant drip-feed. But this drip feed had serious side-effects on capitalism itself.

Consider the following sequence: The Federal Reserve extends new liquidity to, say, Bank of America, at almost zero interest. To profit from it, Bank of America must lend it on, although never to the “little” people whose circumstances – and ability to repay – are diminished. So, it lends to, say, Apple, which is already awash with cash.

Why is Apple saving money, rather than investing it? Because that’s how the company maximises its profits in an environment of low consumer demand. To see this, consider that, since 2008, megafirms like Apple look at their potential customers and see a sea of increasingly impecunious “little” people. Having established a virtual monopoly over the market for their products, such as the iPhone, they understand that to maximise their profits they must restrain their output, so as to create the relative scarcity that boosts prices. Output constraints that boost prices require lower investment which, in turn, results in greater savings for Apple at the expense, again, of the “little people” who are immersed more deeply into precarious jobs.

Nevertheless, despite the fact Apple’s directors do not need the extra cash, when the Bank of America offers them what amounts to free money, they take it. What for? First, the small interest they pay is tax deductible. Secondly, they take the new money to the stock market where they use it to buy… Apple shares. The company’s share price skyrockets and, along with it, so does the executives’ salary bonuses — because they are linked to the company’s share value — as well as the stashes of the ultra-rich holding most of the company’s shares.

Apple is merely one example. The same applies to all large corporations all over the world. Between 2009 and 2020, this process prised stock prices away from the real economy. It was a time when the world of money inflated while the ratio of investment to available cash shrank to the lowest level in capitalism’s history.

The ultra-wealthy grew richer in their sleep, money and power accumulated in the hands of the 0.1 per cent, and a majority of people were held behind. Market uber-power subsequently allowed the uber-rich, and the megafirms they control, to usurp markets, buy justice, capture regulators, pad campaigns — in short, to poison liberal democracy.

That was the state of play before COVID-19 paid global capitalism a devastating visit.

The virus hit consumption and production massively and at once. Central banks felt they had no alternative but to pump even more money into the hands of the banks — hoping against hope that, this time, it would be lent to firms that invest. But why would this trick work during a pandemic when it had failed before?

It did not work and, as a result, the freshly minted trillions of central bank money led to obscene growth of stock prices at a time when average wages, prices and profits were collapsing. This is the reason for UBS’s finding that during the few short months of the pandemic, the world’s billionaires saw their wealth rise by an indecent 28 per cent.

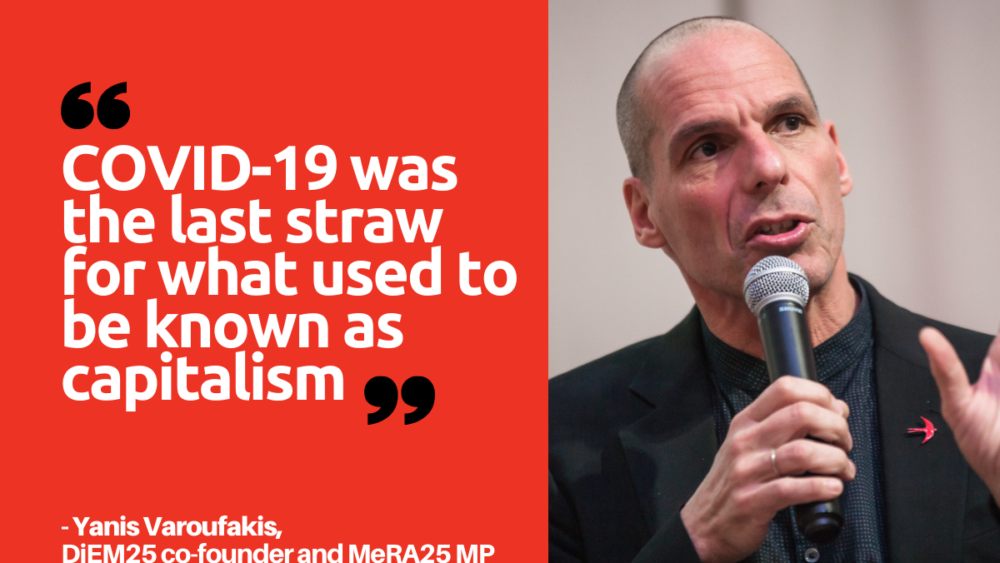

COVID-19 was the last straw for what used to be known as capitalism: the causal link between innovation, profitability, stock prices and capital accumulation. Unbeknownst to both leftists and conservatives, the post-2008 secular stagnation combined forces with the economic impact of COVID-19 to drag us into a variety of post-capitalism.

Why post-capitalism?

Think about it: Capitalism is supposed to be a decentralised system where competition coordinates the decisions of profit-maximising economic actors that are too powerless, individually, to influence the market. Our reality, after 2008, and especially during this pandemic, is nothing like it.

Today, three companies — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — own at least 40 percent of all American public companies and nearly 90 per cent of those listed in the New York Stock Exchange. Tacit collusion is rampant, because every chief executive knows the parent megafirm is likely to be talking to CEOs of rival companies it owns. The result is higher prices, less innovation and stagnant wages. This system, in which Big Tech and the financial sector yield immense power, and the ultra-rich own almost everything, cannot really be described as capitalism. Techno-feudalism comes closer to capturing the spirit of the present.

Under this dystopic post-capitalism, our techno-feudal lords have the power to manipulate our behaviour at an industrial scale advertisers could never even dream of. Moreover, whereas in years past, extreme poverty hit mostly the unskilled, the rural and the marginalised workers, now it is spreading to white collar professionals, to well-educated people stuck at home or in sectors fast declining, to fading city centres, to artists, musicians and people that used to survive well by doing creative things while doing odd jobs.

If I am right that we are already in the early phase of a spontaneously evolved grim post-capitalism, maybe it is time to start designing, rationally and together, a desirable post-capitalism. But where to begin?

First, suppose that was automatically to grant each person a free, digital bank account. Then, instead of lending to commercial banks in the hope that the money will trickle down to the “little” people, the central bank could credit a certain amount to everyone, with the government taxing that sum at the end of the year, depending on one’s total income. The central bank could go even further by granting every newborn an account with, say, $100,000 to be spent as an adult on education, setting up a business or some other creative project – in effect, a trust fund for every baby.

Secondly, central banks can agree to create a digital accounting unit, let’s call it the Kosmos, in which all international trade and cross-border money transfers are denominated with a free-floating exchange rate between national currencies and the Kosmos. This would allow to tax every trade deficit, every trade surplus, and every surge of capital out of, or into, any country, so that Kosmos units accumulate steadily in a Global Sovereign Wealth Fund, which are used to finance green transition projects in developing countries.

While these ideas alone are not a complete blueprint of “another now”, they offer insights into what we can actually do now, instead of merely lamenting the rise of the new feudalism that is threatening our species.

To that effect, I recently published Another Now: Dispatches from an alternative present (London: The Bodley Head), a book offering such a vision, its controversial premise being that only by ending capitalism fully (i.e. eradicating labour and share markets) can a fully-fledged competitive, and democratic, market economy emerge.

This article was originally published in The Saturday paper, as a part of its ‘After the Virus’ series.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here