Filippo Bodini gives his critique on technocracy that is spreading not only in Italy but across Europe, providing wider context using Rodrik’s theory of globalisation

There are many ways to explain the globalisation process, but there are two main classifications: light globalisation, also called ‘superficial globalisation’ and hyperglobalisation, also called ‘deep globalisation’. If the first type is a way to obtain the best globalisation process without dismissing the internal structure of the country and ignoring democratic values, the latter is to overwhelm national sovereignty and democratic process in order to fulfil a desired agenda.

The hyperglobalisation method is more valid in cases where there is both a common target to achieve like saving the earth from global warming and obvious scientific evidence of how to obtain the target.

The more the target is not universally shared and the scientific evidence is blurred, the more the hyperglobalisation must be taken apart in favour of ‘light globalisation’ because there is no scientific reason to impose a set of directives over democratic decisions.

For instance, in the case of this dichotomy, is necessary to pay particular attention to the development of countries: despite Washington consensus agenda, which is a series of points to implement in order to liberalise the markets and allow a country to attract foreign investments, China’s economic growth of the last four decades is not the result of a development strategy based on privatisation and progressive shrinking of state control. The impressive growth is the result of combining capitalism with political control, using imported technologies and knowledge to strengthen the internal structures and playing the globalisation game with their own rules. To make the story short, instead of using hyperglobalization agendas, the Chinese government decided to find its own way. Other countries like Japan, or the Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) did the same.

The European context, unfortunately, is the result of following hyperglobalisation methods in the most dangerous way. During the economic and financial crisis post-2009, balance constraints and sovereignties limitations weakened the power of states to use monetary and financial politics to keep the domestic demand alive, causing even more recession. In exchange for those sovereignty limitations, there were no common policies put in place to fight unemployment in the poorest countries by the European Central Bank. Hence, pretending to control all economies of the Eurozone with a set of rules valid for all countries, regardless of the macroeconomic situation of a single region proved that hyperglobalisation failed on social targets like economic development, unemployment reduction and social stability. Here are some reasons:

First, the status of the economy itself, which is rather an empirical science if compared to physics. Hence, combining the most advanced theories with the democratic process is a good method for defining targets and finding development strategies that are often more accurate compared to transnational directives.

Second, the analysis of the context is so important that some theories fit better in a certain context than another. So, according to Rodrik, a good development economist must distinguish from country to country, from period to period. Keynesian analysis is powerful in explaining issues of aggregate demand and finding solutions in contexts like the European crisis from 2009 to 2020 but cannot foresee the post-COVID inflation caused by cost of primary supply, the solution of which could be found in a better geopolitical equilibrium. If we can show historically that there’s no theory that should be applied every time, everywhere, how can we say the same about European balance constraints?

All the following rules derived by Maastricht treaties are, at best, possible implementations of obsolete fiscal conservatism. If those theories are dangerous in times of recession, the derived rules and constraints are even more dangerous and should be taken apart to avoid systemic stagnation or recession.

Third, the theory that creating economic union and imposing macroeconomic discipline in Europe will bring in the long term friendship and political union between states is historically false.

As Yanis Varoufakis correctly said, in the last decade, the rise of right-wing nationalist parties all around Europe, together with the North vs. South conflict, the history of ants and grasshoppers and the moralisation of debt are clear symptoms that Europe is going to disintegrate. I argue that it’s not only a failure of macroeconomic strategy but a methodological failure of hyperglobalisation, thinking that few experts, ignoring democratic instances, could have the knowledge of what Europe needs instead of allowing democracies to find their solutions for every country. This doesn’t mean that we must resign to any attempt of European integration and fallback to national states but simply understand that a good hyperglobalization strategy requires more effort and more adaptations for each county.

After this acknowledgment, we have the elements to form a critique against the concept of technocracy. Technocracy is linked to hyperglobalisation because it’s a methodology that skips democratic debate and imposes directives like if there is no alternative (TINA), but it’s even worse because it justifies itself with the assumption that knowledge comes from science, a kind of superior knowledge that ignorant and quarrelsome politicians will never achieve.

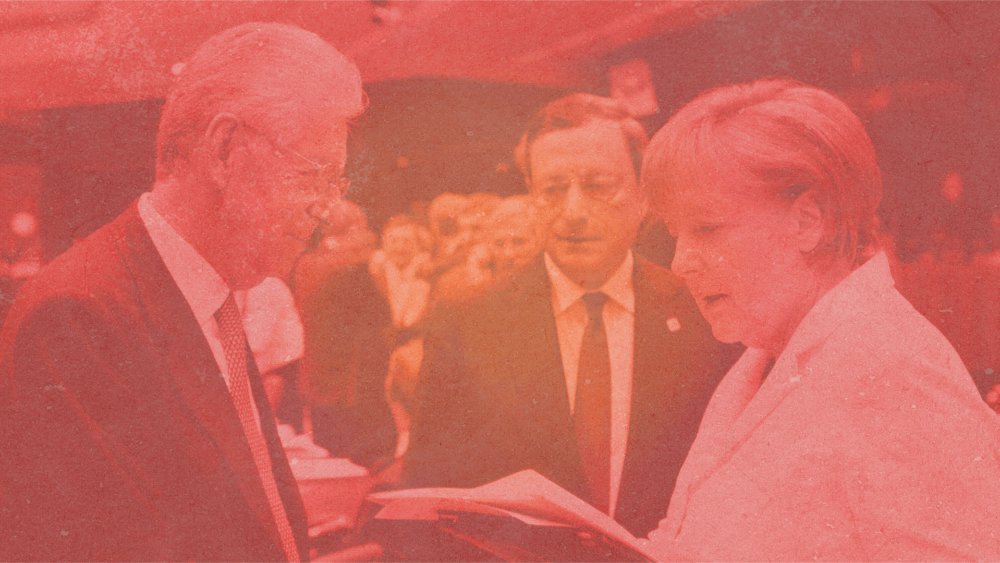

In Italy, during both Monti and Draghi’s government, all the mainstream media started a very dangerous worship of every decision taken, without any condition where you are allowed to make some criticism or disapprove their actions. This leads to a logical problem for democracy itself: if there’s only one correct way to save the country, why is the democratic debate necessary?

Fortunately for us there is no superior knowledge, they failed as any politicians failed. Monti was introduced to avoid recession: after Monti’s government, the economy collapsed and the media said that he saved us from the worst possibilities.

Draghi’s COVID politics are a total failure: putting all effort on vaccines and ignoring or even hindering the cure gave an output of deaths similar to any other country and the green pass increased social tensions like no other country in Europe. So, in order to fight technocracy every citizen should understand that this kind of authoritarianism is justified only for a very tiny set of problems and only if science is true science, not the politicised type. Instead, for the largest amount of problems, we must aim to have a better political class instead of technocrats. Economic development strategy is not a “standalone technical process” but rather an empirical science influenced by particular political contexts, linked to social disciplines, hopefully inspired from political philosophy and the need for a holistic approach and democratic debate.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here