61 million women and 47 million men in the European Union are living with disabilities.

The United Nations proposes in 2020 to ‘build back better’ “toward a disability-inclusive, accessible and sustainable post COVID-19 World”. For EU member states, the competence to act politically is shared between the bodies of the European Union, the States and each geographical level they have chosen, from the region to the city/village. In this report we will present some of the issues that people with disabilities face during the COVID-19 pandemic in the EU.

Since the Council of the European Communities in the 1970s, Europe has been investing in people with disabilities, and more ambitious projects have begun more recently, such as: The European Disability Strategy 2010-2020. As planned, an end-of-stage report has been published, taking into account the COVID-19 pandemic.

The analysis we propose below was made using the human rights model of disability as a canvas (to be discussed later), although most of the countries in Europe have been using the social model of disability for thirty years. Indeed, “Instead of using the person with disability as ‘having something wrong’ that needs to be ‘fixed’, the social model sees society and the barriers it places to the aspirations and progress of people with disabilities as being at fault.”

The human rights model of disability recognizes that: “People with disability have the same rights as everyone else in society. Impairment must not be used as an excuse to deny or restrict people’s rights”. It should be considered an advantage for persons with disabilities to use both models to overcome barriers and discrimination, and sometimes segregation.

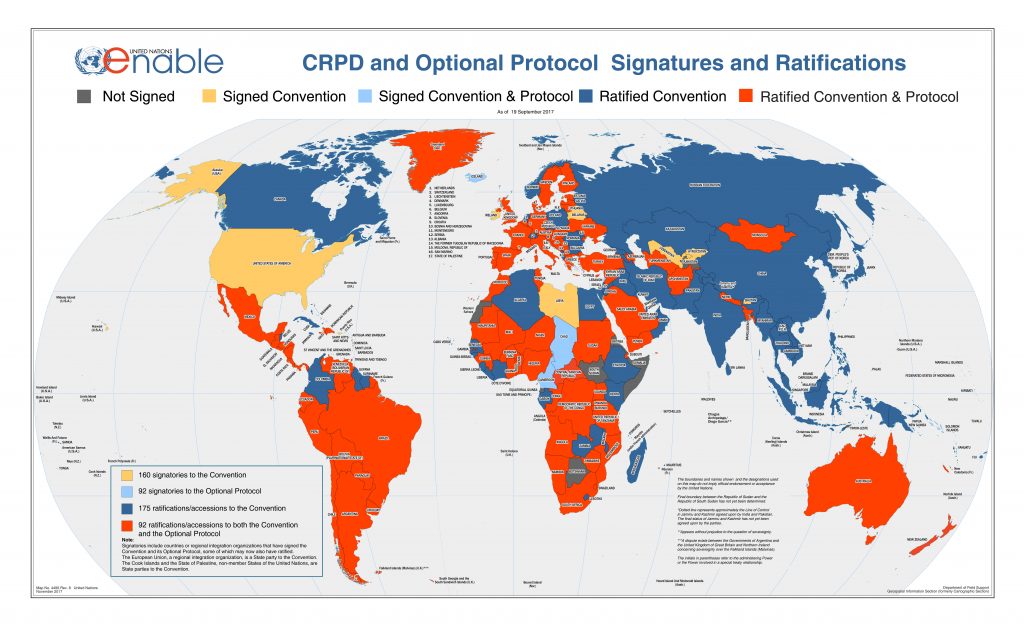

These Human Rights principles are set out in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and here is a map of the countries that have ratified it, you can include the European Union itself.

Without preventative public health policy, people with disabilities are more vulnerable when faced with pandemics.

Equality and non-discrimination – Article 5 – is the core of the Universal Human Rights. According to Amnesty International, “discrimination occurs when a person is unable to enjoy his or her human rights or other legal rights on an equal basis with others because of an unjustified distinction made in policy, law or treatment”.

It’s a double punishment, some people with disabilities and higher risk of complications as well as elderly people have an increased likelihood to die from COVID-19. And yet they were discriminated against! In France, part of our population was locked up in psychiatric institutions and staff were neither trained nor equipped to deal with any epidemic. It was the same when emergencies were called; institutionalised patients were told not to go to hospital!” What happened to the champion of public health? What happened to the preventive public health policy with its multiple pandemic plans?

The Taskforce for Feminism, Diversity and Disabilities and the ONG Inclusion Europe have also seen the need for governments to be deliberate and conscious when giving messages around vulnerable and at-risk groups so that they do not stigmatise or “other” these groups. Instead, we should always be explicitly recognised as an integral part of our communities.

Most countries are in breach of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the situation needs to change.

Equality before the law – Article 12 – is the instrument given to people to defend their interests and access legal services (including private services, such as banks). Guardianship and trusteeship should not be considered if it is imposed on people with mental health problems (a medical analysis is subjective and culturally dependent).

During the spread of the COVID-19 virus, the main concern was the medical relationship. Taskforce members and our relatives personally witnessed many cases of psychiatric and/or medical treatment given without the free and informed consent of the patient. And often without explaining or giving other choices, without empowerment, even if the patient was fully capable of understanding his or her condition.

With the exception of DiEM25 and its partners, no one has realised that healthcare and education cannot be thought of in neoliberal terms.

The participation of persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organizations, in the implementation and monitoring of the Convention – Articles 4.3 & 33.3

In the EU, there is a fundamental problem for the advancement of the rights of people with disabilities: one of the conclusions of the Disability Strategy 2010-2020 is that there is a “lack of a clear baseline data set” to monitor progress. The only way to evaluate is therefore through qualitative means. This is even more problematic given that it has been recognised from the outset that the strategy will take time to show results (see reference above).

As all our countries implement health care protection and education differently, there is no system in place for collating data from all EU partners. The social pillar of the EU that started in 2017 is the sad reason for this.

Persistent violence against women and girls with disabilities includes sexual violence and abuse, sexual and economic exploitation, forced sterilisation, institutionalisation.

Women and girls with disabilities – Article 6 – is one of the many forms of intersectional discrimination. It “recognizes that individuals do not experience discrimination as members of a homogenous group but, rather, as individuals with multidimensional layers of identities, statuses and life circumstances. It acknowledges the lived realities and experiences of heightened disadvantage of individuals caused by multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination […]”

Women with disabilities are composed of various groups — from different ethnic groups and/or are migrants, in detention, in poverty and/or are lesbian, bisexual, transgender.

Because sexual exploitation is slavery and it is a question of ethnicity, age, gender, social class, so many intersectional discriminations can be combined. And the more sexual violence strikes, the more deeply the brain and the body are dissociated. Although prostitution has probably decreased during the pandemic, because physical contact has been avoided, there is a strong need for health and financial support, because sex workers are stigmatised.

The pandemic has shown that communities of care are crucial for well being.

Living independently and being included in the community – Article 19. Independent living is “having the right level of support to do the things you want to do with your life” and it highlights the way in which we are interdependent with each other, in no way seeking a ‘paternalistic approach to service provision’.

During a pandemic, we rely on supporting networks of mutual aid at community level (such as family, neighbourhood shoppers, medication and food deliveries, local social media contact trees, nongovernmental organizations) so as to build and reinforce community cohesion.So does the DiEM25 Green New Deal for Europe, with the care income.

It follows that the state must foster community cohesion and provide free public health care to minorities on equal terms, equipped to deal with economic and health crisis.

Governments have implemented many temporary financial measures, such as the extension of financial aid, funds to support the additional purchase of medicines and protective elements. Has this basic income been so difficult to implement?

The extension of the obligation on employers to make “reasonable adjustments” for disabled employees so that it includes more options such as home working, flexible hours, especially for those people whose disability involves chronic energy depletion (e.g. chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis, systemic autoimmunity, fibromyalgia).

Accessibility – Article 9 – concerns including the physical environment such as transportation, information and communication services as open to the public. In the UK, our envoy pointed out that those “left-behind” and most “vulnerable” are poorly informed as to what to do during the crisis and not included in important decisions for example the impact of releasing the lockdown too early. In France, an advertisement by a non-governmental organisation set the framework by comparing social distancing with the situation of a person with disabilities: “Mobility, accessibility: now you know what it is.”

The disruption of the education system has exacerbated all the problems that children and their families face.

The right to inclusive education – Article 24. The inclusive education programme must be tailored to all forms of disability, made available in accessible places or media, in a spirit of acceptance for the benefits of all.

Although e-learning can benefit the child’s ability to search information personally, there is no guarantee that educational material is par for the course. Parents’ responsibilities have increased and social inclusion has decreased. There is therefore an urgent need to open schools with all support staff. And not to delay the opening of specialised schools or branches, as is the case in many countries.

We have seen some of the problems affecting people with disabilities in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic with alternating periods of physical distancing.

Most of the cases show a negative impact that was probably worse for people with disabilities living on the street, migrants with disabilities, people with disabilities living in European countries facing an economic crisis. Two independent studies demonstrate that Europe was the highest contributor to the intercontinental spread of the virus. As 80% of people with disabilities live in emerging countries, it would have been wise to set the first wave of pandemic lockdowns much earlier in Europe.

On the international day of persons with disabilities, we call for an urgent revision of COVID-19 measures that not only take into account the various aspects mentioned in this article, but also include persons with disabilities in democratic processes of decision-making. The pandemic has also showcased that we can no longer “other” certain groups — everyone going through this health crisis can attest to the need for preventative public care, a care income and/or solidarity cash payment, and of investing in networks of mutual care and community cohesion.

At DiEM25, we address these issues through our proposal of a 3-Point-Plan tackling the pandemic, and our Green New Deal for Europe which emphasises intersectionality at the heart of a just transition.

Photo Source: Photo by ELEVATE from Pexels.

Please contact the Taskforce for Feminism, Disabilities and Diversity, if you want to be further involved.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here