Today is World Autistic Pride Day, an international celebration, promoting understanding and acceptance of autism, established in 2005.

Autism Spectrum Disorder is a condition that has recently been a subject of cultural debate following the release of the music video “Music” by the global, semi-anonymous superstar, Sia. The video and the response to it highlighted the difficulty that filmmakers experience in attempting to accurately capture the experience of a person with a condition such as autism spectrum disorder, which varies considerably from one individual to another.

Portraying an extreme case of autism arguably does more damage than good by perpetuating unhelpful stereotypes. However, this controversy might have been avoided had the singer not cast a non-autistic actor to play the role, which seems to have been the root of most of the backlash.

What is autism?

Autism Spectrum “Disorder” is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition that can manifest as early as three years of age, with between one and two per cent of the population in Europe having been diagnosed with it. However, because of conservative practices, only 15% of all autistic people are diagnosed in France, when compared with the expected number of autistic people in the population, 700,000.

Stereotypes of autistic people have existed for centuries. For example, autistic people were described by a Brit, John Langdon Down, in 1887 as “idiot savants“. The term “autistic” was first coined in 1908 by the Swiss Eugene Bleuler, to describe another condition. In Russia, 1925, Grunya Sukhareva was the first to associate the term ‘autistic’ specifically to the autism condition, using accurate scientific terminology, though she is yet to be credited for this work. And to say that the use of the word autism to describe this condition, whose etymology means “self-enclosure”, is the usual mark of contempt shown by the medical profession. Given its diversity of symptoms, the word “autism” fails to accurately encapsulate the range of experiences that autistic people have.

Furthermore, “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, as defined by the medical community, is classified as a mental health trouble. But, if many autistic people have comorbidities of mental health troubles, like depression or anxiety, some have no mental health issues at all.

Autism is a term that encompasses a spectrum of symptoms. Half of all autistic people have a cognitive disability, 30% have minimal verbal skills, 70% have (the abandoned label) Asperger’s syndrome and half of autistic people have varying difficulty interpreting their emotions.

Furthermore, the image of autism as a “disorder”, and the connotations associated with that framing, is one that is commonly portrayed by the media, the scientific community and, sadly, many non-government organisations. As a response, the autistic movement has empowered itself through the promotion of the concept of neurodiversity developed by Judy Singer, representing all the diverse ways of thinking present in humans, with celebrities such as Temple Grandin and Stephen Wiltshire advocating for more accurate representations of autistic people in the public space.

Gender, gender orientation and ethnicity discriminations

For women, ethnic minorities and LGBTQIA+ autistic people, the challenges are even greater. They often experience delays in being diagnosed compared to their white and/or male counterparts, and in some cases remain undiagnosed for life.

Worldwide, girls are three times less likely to be diagnosed on the spectrum than boys. Although these diagnostic biases were observed as early as 1995, the problem is still yet to be addressed. This diagnostic imbalance may be largely as a result of an as-yet unexplained potential genetic trait, which better allows girls to camouflage their social communication difficulties. Failing to diagnose an individual as autistic can have severe consequences for their wellbeing.

By their very nature, undiagnosed women are not included in official statistics about autistic people, which can often downplay the scale of the need of the autistic community. For example, only 22% of autistic people are in work, compared with 80% of people who are not autistic. However, this 22% isn’t even taking into account the likely many undiagnosed people, which would make the figures far more sobering than they already are.

In some cases, this can be the difference between life and death. For this woman, (trigger warning) making the connection between her autism diagnosis and her Patau’s Syndrome could have helped her to receive adequate medical care. Instead, she died of starvation in hospital.

Unfortunately, the UK is currently the only country in Europe that collects data on ethnic minority autistic people, meaning that there is a gaping deficit of data for the rest of the continent. Based on the evidence that we do have, however, it seems that in the UK, ethnic minorities are frequently misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed in special schools. And although there are no studies as of yet in Europe, in the USA ethnic minorities children have more difficulties in being diagnosed and thus do not receive adequate support.

About transgender and gender diversity, LGBTGIA+ autistic people face increased discriminations. Since autistic people are simply more comfortable identifying as trans and gender diverse, there is no need to systematically pathologise what does not fit into the norm. And this is unfortunately the case in too many studies.

For ethnic minorities, misdiagnosis occurs frequently with other conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity “disorder” – ADHD or conduct “disorder”. For women and girls, misdiagnosis in part occurs because of the assessment method: selected criteria have been chosen on male interests only. In both cases, misdiagnosis is likely to be due conjointly to the specialist and the family/teachers describing the children or the childhood.

How do autistic people communicate and feel?

To begin with, autistic people have very different conditions, but there are some common characteristics, and these characteristics may change over time, depending on the child’s intellectual abilities. For example, as children age, many mental tasks become automated in the non-autistic population. This is not quite the case for autistic people.

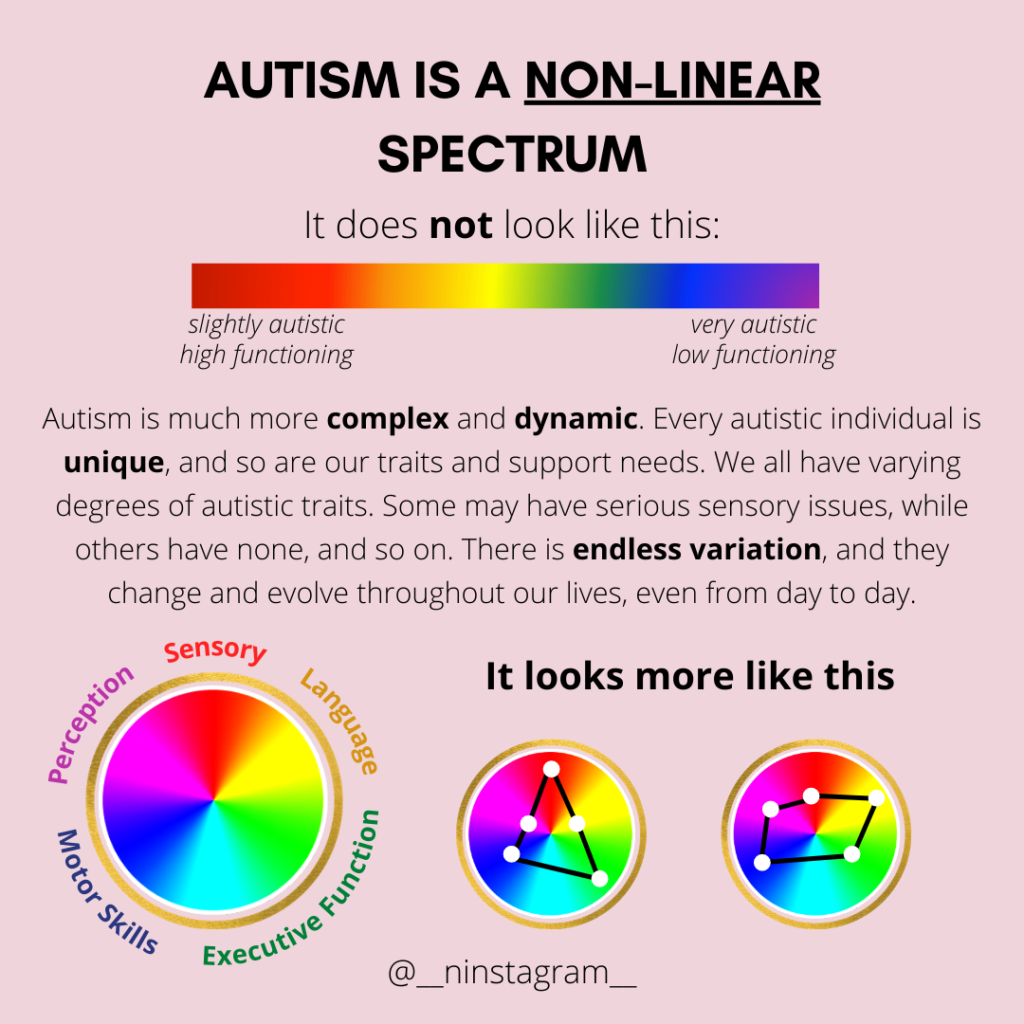

As a useful guide, the upper part of this figure (see below) summarises the main characteristics of autistic individuals.

And the circles illustrate the differences we have in communication and social skills (language, executive function) and sensory skills (senses, perception, motor skills). Illustration courtesy of Nina Skov Jensen.

Communication and social skills

Each region of our brains are devoted to special tasks, such as speech recognition, the process of identifying specific sounds as messages and then remembering them, and later recalling that information, and associating it with specific movements on a speaker’s face.

From childhood onwards, specialised areas of the brain have to connect to each other to do the job. Some “wiring” is very fast, whereas some is slow. That is the distinction between white or grey matter. On the autistic spectrum, there is a difference in the way that grey matter and white matter is distributed in the brain, which affects information processing in autistic people.

Senses

The senses include sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste, balance and self-perception of one’s organs, because equilibrium, ability to catch things etc, and sensitivity to colour can be modified in autistic people. On the autism spectrum, certain senses are enhanced or inhibited, depending on the context.

For example, when listening, the brain usually filters out unwanted noises that may affect a conversation. Autistic people, however, filter out sounds to a lesser degree, which in fact leads to better musicianship; in other words, it becomes easier to feel the music. Difficulties arise, though, when confronted with loud, sudden and unwanted noises and when trying to distinguish speech in a noisy environment, such as an open plan office.

Most of the repeated movements that autistic people sometimes make or the concentration on particular subjects, are, in some way, a means of distracting one’s senses and thoughts to relieve emotions, or to better focus.

Later in life, it seems that these differences and attention-to-detail allow for positive traits such as systemisation of information, and an enhanced capacity to see the bigger picture.

What has to be done?

In its Green New Deal for Europe, DiEM25 promotes both a minimum standard for affordable public health care as well as care income (GNDE section 3.1.1 and 3.4.3). Although there is no specific mention of autistic people, support may be necessary, as though not all autistic people require care or support, some do, and this should be accounted and provided for.

To enable access to work, as with all disabilities, companies must respect their obligation to employ disabled people. In France, Italy and Spain, the laws are too lenient and companies prefer to accept the minor inconvenience of a small fine. Furthermore, the diagnoses of many autistic people who consider themselves to be disabled are not recognised by administrations.

Making public education (i.e. schools, universities etc) more adaptable and “neurodiverse-friendly” is also essential. In the UK, the legal requirement is to consider autistic people “disabled” and therefore public bodies and employers must make “reasonable adjustments” to their services to accommodate them. But this is far too weak a requirement.

We need a revolutionary approach that starts with the assumption that all are entitled to equity of access; designing schools, universities around the needs of people, rather than “adapting” ableist spaces and services, only when disabled make a fuss.

As we have seen, the failure to diagnose autistic women, ethnic minorities and adults is a glaring problem that is yet to be addressed. This problem cannot be addressed solely by compensatory incomes or job positions where skills are undervalued. Diversity has to be based on acceptance, of our differences and our complementarities, at the workplace and outside the job. In other words, it is not only a working class issue.

An individual may be oppressed or stigmatised for a variety of reasons, however, responses to oppression tend to focus solely on a singular identity characteristic. It is precisely at the intersection of identity groups that we must look for what unites us. The queer, physically disabled Korean transracial and transnational adoptee writer Mia Mingus calls it interdependence, and it has always applied to all of us.

If you want to know more about the topic, there are many activists on social networks who help both diagnosed and undiagnosed people, as sometimes diagnosis or support is a cost not covered by the authorities. We recommend that you follow the disability advocate Tiffany Joseph.

Contact of the DiEM25 Task Force on Feminism, Diversity, and Disabilities: fdd@diem25.org

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here