Housing costs are the largest monthly household expense for most Europeans today. Indeed, in most EU member states, housing costs are growing at a faster rate than wages.

The increase in homelessness across the continent shows the lack of a coherent policy response to this issue.

Investment in public housing in Europe was dramatically reduced between 2009 and 2012. In 2011, there were 38 million vacant apartments across Europe. In Germany alone, 2,14 million apartments were vacant in 2017. At the same time, homelessness increased in all European countries (except Finland) and reached record highs across the continent.

In addition, vacancy rates in Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Malta, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Spain and Italy account for around 30 percent of all apartments. This is partly due to the fact that many flats are used as holiday accommodation, driving up rents for local populations. The shortage can also be felt in German cities due to the permanent letting of apartments to tourists.

Lack of infrastructure in rural regions leads to rural exodus.

There are further tensions due to the declining number of jobs and the lack of digital infrastructure in rural areas. A lack of public transport, irregular rail services, closed train stations in smaller communities and a lack of schools and hospitals, all play a part in driving young, well-educated people to large cities.

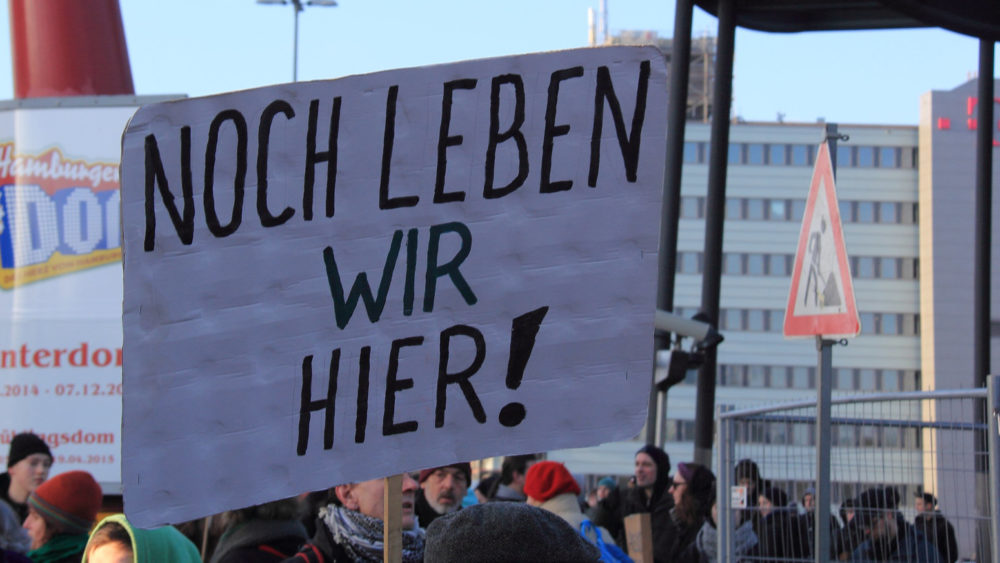

Due to the exorbitant rise in housing prices and the social pressure from citizens’ initiatives such as “Deutsche Wohnen & Coenteignen” (the initiative to expropriate large corporate landlords in Berlin), signed by DiEM25 co-founder Yanis Varoufakis during his European election campaign visit to Berlin, the Berlin Senate (consisting of Social democratic, Green and Left parties) has now introduced an unprecedented amendment to the law concerning Statutory Provisions on Rent Limitation (Regelungen des Gesetzes zur Neuregelung gesetzlicher Vorschriften zur Mietenbegrenzung” – Mietendeckel). This law is intended to freeze rents in Berlin for a period of five years. Excessive rents are to be capped.

Among other measures, the law provides above all for a combination of a rent freeze and rent caps.

This law will apply to 1,5 million apartments built before 2014. There will be an upper limit of EUR 9.80 per square meter. This exact value will depend on the year of construction and the facilities and equipment included. The law should not only slow down the fast increase in housing prices, it should also reduce rents to a more socially acceptable level.

Can the rent control model adopted today in Berlin serve as a model for other major European cities?

It is not only in many major German cities that people are following closely the developments of Berlin’s housing policy. Javier Buron, housing manager of the city administration of Barcelona, writes:

“In Barcelona, the current events in Berlin are followed with great interest. The prospect of a city with a reliable public system for measuring rental prices (rent index) and the political will and technical ability to initially limit market price increases (rent brake) and completely freeze rental prices for five years is of the greatest interest to Catalan activists, legislators, the media and public managers.

Barcelona already has a system similar to the rent index (“Index de preus de lloguer de la Generalitat de Catalunya”), but the local authorities are faced with a hesitant Ministry of State that does not intervene in the market and does not allow local authorities to do so. Even though the rental markets in Berlin and Barcelona are very different (less public stock), the performance of the new Berlin model is very relevant for the struggle for social and affordable rent in Barcelona.“

Meanwhile, as expected, the real estate industry has begun its criticism of the plans because rent controls will have a considerable effect on their profit margins. We see the current initiative as a first step towards securing affordable rents for all.

Housing is a human right, not a commodity.

The housing sector should not serve profit maximisation, but rather the common good. A non-profit housing sector is possible!

A reintroduction of non-profit status (“Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeit“) (abolished in the 1990s) must remain on the housing policy agenda. Land should be converted into leasehold rights while retaining private ownership so that building projects can be regulated in the public interest (examples: Vienna, Amsterdam). We need a municipal planning law, municipal land policy, municipal regulation of the housing stock, a new non-profit status for the housing companies, housing construction as infrastructure planning and local alliances for affordable building and housing.

Rent caps should only be the beginning. The path to a paradigm shift requires the transformation of private property into common property. These local measures must be part of a European perspective, as we have designed them in our DiEM25 Green New Deal for Europe.

The 5 year limitation period is not the only pitfall of the current solution. The expected legal disputes threaten to dilute the aim of the “rent cap”, if not substantially undermine it. On the occasion of the reform of the land tax, which has just taken place, the transformation into a land value tax was neglected, further aggravating the situation.

Whether rent levels fall as a result of the law or at least cease to rise further, it is a example for governments in other cities and a light on the horizon for the tenants of Europe!

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here