Ivana Nenadovic reflects on her experiences of the brutal Yugoslavian wars, which have come surging back amid the current catastrophe taking place in Gaza, as a familiarly toxic war gets underway and where humanity is disregarded

I’m overwhelmed with the news and images from Israel and Gaza in the last two weeks. My heart is breaking for every lost life, for every mother who lost their child.

While I’m listening to both sides justifying their actions, from the western mainstream media spins that fuel polarisation, to the independent journalists on both sides being targeted and silenced by their governments, or the humanitarian organisations and academics mincing their words to condemn one side or the other, to support one side or the other, while trying to express the empathy for both sides, succeeding only in cancelling each other.

I’m finding myself triggered by the propaganda and frustrated by a very naïve understanding of the war in intellectual circles, but I do salute them for trying their best to be a moral compass in the centre of the storm. My perspective is lacking the necessary academic knowledge to reference the historic events and to quote the world leaders, instead my ‘expertise’ comes from my experience. An experience I wish I didn’t have.

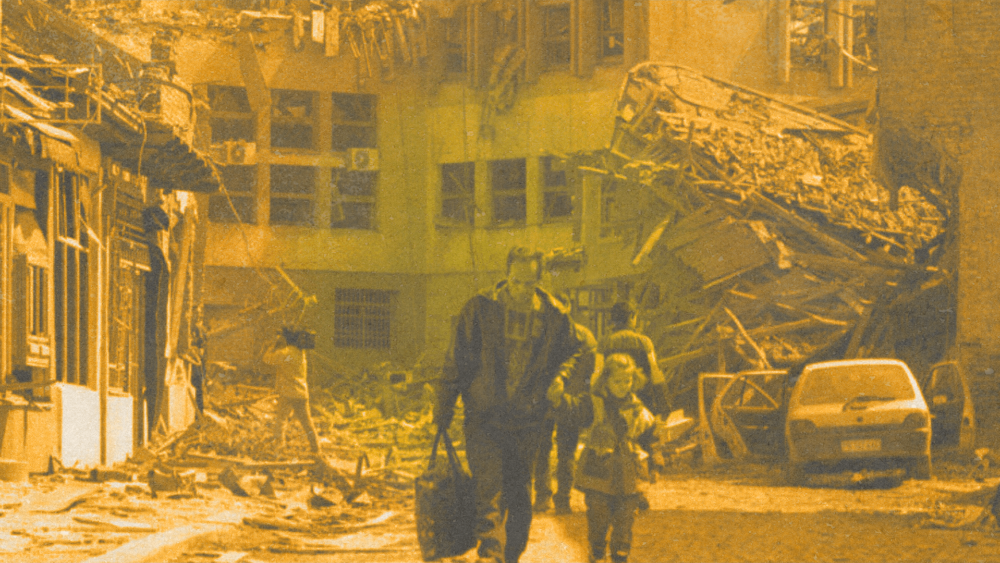

I remember one of the nights during those three months in 1999 when the airstrikes were especially intense on Belgrade. On that night, my brother (20) and I (22) were lying on our beds, windows in our room were duct taped with big ‘X’s, so that the glass wouldn’t smash in case of a detonation. We kept our windows a bit open for the same reason although it was cold. We already knew how to tell the difference between the sound of an aircraft flying over, or breaking the sound wall, and a detonation. We also knew that if you heard a missile approaching – Tomahawk was ‘our’ brand – that sound is most likely the last thing you are going to hear.

At first, I heard the humming, and as it got closer and louder, I also heard the squeaky sound of a missile, a sound you don’t forget once you hear it. In a speed and strength I never imagined I possessed, I pulled my brother down from his bed and I laid on top of him. My biggest fear was not so much of dying as it was of being cut by glass or badly wounded, as ending up in a hospital would be worse than dying, I thought. Hospitals were already unequipped thanks to decade long sanctions and now they were overwhelmed with wounded people. After a couple of seconds, which lasted like hours – those moments when your life unfolds in split seconds – we realised that, what we thought was a fatal hit, flew over us on its merry way to its target.

As we found out later, that night another infrastructural target was aimed at – a powerplant in New Belgrade, just across the river from our apartment, providing half a million people with heating. Powerplants were a regular target so we were already experiencing power cuts which were followed by the water cuts because the pumps cannot work without electricity. Infrastructure used for civilians’ [basic] needs was regularly targeted under excuses of either ‘prevention of the military actions/ethnic cleansing in Kosovo’ or, in case of the bombing of Radio-Television Serbia (RTS) where 16 employees were killed at work, ‘to put a stop to Slobodan Milosevic’s propaganda being spread’.

NATO headquarters were warning for days that they would bomb the ‘Television Bastille’ to stop the, indeed, horrific narrative coming from Milosevic’s den. The news and ‘political’ programme have already been moved to broadcast from a different location, but the employees were still made to come to the main building which was a target. If employees would decline to come to their ‘shift’, including night shifts during the air raids, they would be fired. Only a ‘lucky break’ saved my mother, who was a news presenter at RTS, from going to those shifts as, just before the bombing started, she broke her leg. My parents were handling the whole period of bombing calmly, which in a weird way made me feel safer, but on that night, when I saw my parents breaking down in tears as we watched a live reporting from the RTS building in flames, with bodies hanging from the ruins, my heart sank. My mother knew and worked with some of those people, the spot where the Tomahawk hit was exactly where the make-up room was, where I used to sit in a big, red chair watching my mum get prepared for the news, as she would sometimes bring me with her while I was a child.

Under the conviction of the current Serbian president Aleksandar Vucic, who was a minister of media in Milosevic’s government at that time, that “they won’t strike while people are inside”, employees of Radio-Television Serbia were sacrificed that night when the warning to Serbian government was issued by NATO but the government chose to leave the people in the building – because it was good for PR, to use it as a proof of how brutal the ‘military intervention’ was.

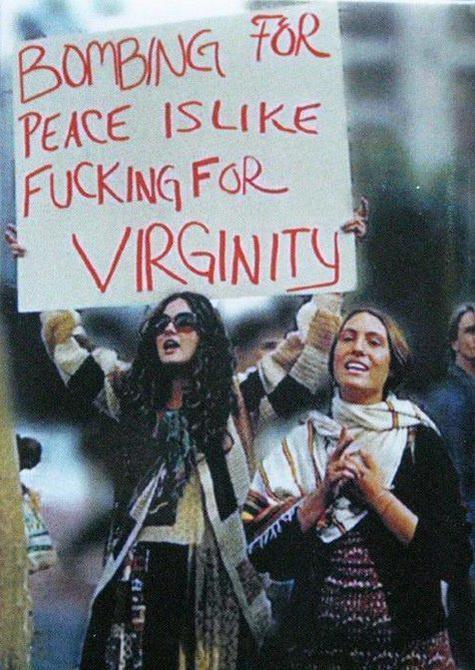

In parallel, it’s also true that ‘surgically precise’ missiles would ‘misfire’ and hit civilians – refugees, fleeing from their destroyed homes – as it is also true that the ‘Kosovo liberation army’ would conduct atrocities, as a revenge for some other atrocities that were done by ‘genocidal Serbs’. And, very soon, one would get entangled in the hellish ‘who started it’ debate, in rage, despair, constant fear for life and powerlessness over the invisible enemy.

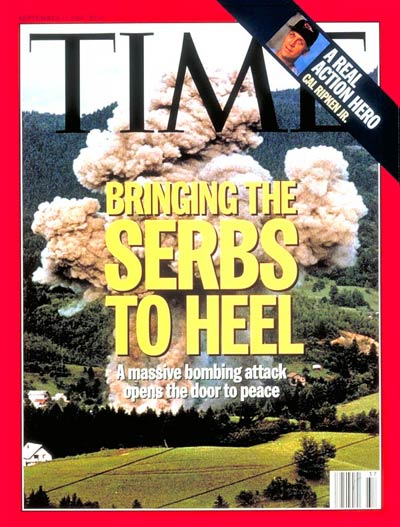

At the same time, division was growing bigger within the impoverished society, within families, between those who ‘would rather see us all extinct than surrender’ and those who were determined to fight and beat Milosevic’s murderous regime, which cost Serbia its best – young boys, 18 years old, who were deployed and sent to the war zone as cannon fodder or, if they were lucky enough, those who escaped the country. Decade-long sanctions, thousands of dead and hundreds of thousands who left, topped off with the bombing of civilians, were not helping rational thinking nor was it helping us, those citizens protesting for peace and against Milosevic since 1991, to justify the brutal western propaganda and sotonisation of the whole nation. Over the time, rare voices from abroad who were trying to ‘stand with the Serbian people’ – not with Milosevic and his regime – were quickly silenced as supporters of the ‘genocide conducted by the Serbs’.

The power of western propaganda machinery against Milosevic, which we were able to witness with our own eyes on CNN or BBC, was excruciating to watch. It was impossible to make a distinction in the media’s narrative between the government of Serbia and the people of Serbia: footage of Milosevic’s generals and supporters was all over the news, depicting all the Serbs as savages. A picture that persists to this day.

The world moved on, a new US conquest was on the horizon, while Serbs were left to ‘learn how to behave’ before we were considered worthy of the civilised EU. Even in DiEM25’s utopian vision of the future, Europe is still just the EU. Even in DiEM25, war in Ukraine is ‘the first war on the European ground since WWII’. The same WWII when concentration camps were ‘for Jews, Serbs and Gipsies’, in one of which both of my grandfathers were killed. However, no one found it outrageous when a German, Joschka Fischer, a leader of the German Greens, was calling for the ‘final solution’ for the Serbs. No eyebrows were raised when a young German DiEM25 member, surprised that I’m in DiEM25, told me that he thought that all Serbs are fascists. Nor when a young Albanian from Kosovo sent me a message that I should stop masking nationalism in pacifism and that the killing of civilians was necessary, after I talked about peace in DiEM25’s livestream.

Even in DiEM25, among people who call themselves leftists and progressives, I’m put in my place by a comrade with ‘whataboutisms’ whenever I try to speak about the horrors on BOTH sides, without justifying any of them. Even among comrades who talk about unity but also think that there is no space for a thorny Serbia in the EU garden. Even among those who are supposedly standing for equality, my voice is openly considered irrelevant. In my whole life, I was never so discriminated against based on my nationality as I was in the last seven years in DiEM25. I gave my all to counter the narrative, to advocate for peace and common sense, but with no luck as my comrades bought the propaganda although some of them were not even born when the Yugoslavian wars started. Others who might remember it, those who are obsessing over ‘standing on the right side of the history’, some of them Labour and the Western democrats’ supporters – were advocating for the bombing. And I do understand that, I do. Power of propaganda won, and it’s still entrenched in people’s minds and, while Milosevic is long dead and buried, Serbian people are stigmatised for generations to come.

The propaganda is as strong as the power that one side holds. The power of the strongest interest will win the war, a war without winners, where people are dehumanised, where human beings are ‘collateral damage’, where the hatred is deeply rooted in the soil, as deep as depleted uranium. The winners will write the history books and those who lost someone will never forget. Some might forgive. At best, hatred will grow into suppressed frustration and animosity.

Of course, let’s not forget the playbook and that the goal of the US and NATO military ‘interventions’, followed by sanctions, like the ones we’ve seen in the last two decades, from Iraq to Syria, are to make ‘the people’ rebel against their ‘dictator’. A dictator who usually opposes US imperialism and colonialization, but still a dictator – for their own citizens. Bombing made our dictator even stronger, at least until 2000 when he was overthrown in what you would call a ‘colour revolution’. How that turned out, and how our democrats failed us – us, who fought our own parents over who votes for whom, and how come that, 23 years later, we ended up under a rule of a warmonger with Nazi rhetoric backed up by the European Union, is another story. But the harsh truth is that we are nowhere nearer to peace in the Western Balkans, while we are waiting for Bosnia and Kosovo to explode, again.

A sad truth is that ‘all is fair in love and war’. No conventions, no UN resolutions or legal definitions of war crimes or collective punishment apply once the dogs of war are unleashed. There is no logic, no common sense and certainly no nobility in a bloodshed. There is no court martial for the US and NATO war crimes around the globe – they are the winners, and losers do not deserve justice. Violence breeds violence, and the death of human empathy is a telling sign that the proud Western civilisation is sinking [back] into barbarism.

In a world of either or, of black or white, where all Muslims are terrorists or all Jews are Arab-killing Zionists, or the only horror threatening the world is Russia (not Putin – Russia), I’m afraid of the escalation, of the wave of violence and religious fanatism from all sides spilling over to the streets of European cities. I’m afraid that, while we are standing on our high moral ground, we are not seeing how close the tide of war has risen and we might be missing a chance to prevent the flood. The little faith I still had for the humanity is fading away but I’m still holding on to the last grain of hope – DiEM25’s Peace policy.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here