The lack of nuclear disarmament in 2021 constitutes a global failure to address this continuing existential threat to humanity

As of 22 January 2021, nuclear weapons have become illegal under international law with the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) entering into force.

The accord is rightly celebrated as a “historic milestone” (UN Secretary-General António Guterres) of nuclear disarmament legislation, and a beacon of hope for anti-nuclear groups around the world. Furthermore, it constitutes an important act of solidarity and mutual collaboration among participating nations. However, it’s real world effects on the reduction and elimination of nuclear weapons still remain rather dubious.

As Noam Chomsky has warned, the threat of nuclear war should be taken very seriously. Nuclear weapons remain one of the three most pressing potential causes for the extinction of humanity. Chomsky underscores that it is a “virtual miracle that we have survived, not only from numerous accidents but also from occasional very reckless acts of leaders”.

William Perry, a leading authority on nuclear security issues, has a long history inside the walls of national security departments and the corporate boardrooms affiliated with them. He came out of his retirement a couple of years ago to warn the world that:

“[t]oday, the danger of some sort of a nuclear catastrophe is greater than it was during the Cold War (…) and most people are blissfully unaware of [it].”

The world is facing a double threat with regard to nuclear weapons; the danger that they pose in and of themselves as well as peoples astonishing lack of attention to that danger.

From first steps at the UN to the Non-Proliferation Treaty

The first official act of corroboration on the threat of nuclear war occurred on 24 January 1946 in the United Nations General Assembly, passing its first ever resolution by 46 votes to null. It called for the “Establishment of a commission to deal with the problems raised by the discovery of atomic energy”. This initial call on the UN Security Council to work on eliminating nuclear weapons failed as more of the Permanent Members of this group acquired them over the next two decades. However, in the following years constant civil society pressure, the 1958 standoff over Berlin, the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and further proliferation of nuclear armaments began to create an impetus for the necessity of nuclear arms control treaties.

This momentum led to agreements placing limits on the United States and the Soviet Union regarding their nuclear arsenal, delivery and defensive systems. This began with the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972 (ABM), which placed a cap on missile defenses on both countries, amongst other limitations.

Further negotiations in the 1980s established the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) that saw the prohibition of land based ballistic and cruise missiles with a range of 500-5000 kms — while excluding air and sea-based systems. This led to the destruction of nearly 2700 nuclear weapons. Next came the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) that saw a decrease in nuclear armaments of the Soviet Union/Russia and the United States between 1991 and 2009. While successive negotiations on START II and START III failed, the United States and the Russian Federation inked a bilateral treaty in 2010 — New START — that further reduced the deployed nuclear arsenals of each country to 1550.

In the interweaving years however, the ABM and INF treaties ceased to exist due to the withdrawal of the United States in 2002 and 2019 respectively. This means that New START is the only remaining nuclear weapon arms control agreement between Russia and the United States — with both countries accounting together for more than 90% of the global total. Recent reports from the Kremlin and the White House indicate that New START will be renewed for a further five years into 2026. Unless both parties agree on an extension, this last limitation will expire in only a few days time — on 5 February, 2021!

Multilaterally, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was expected to stem the increase of nuclear weapon states. It further placed an obligation on those that possess them to engage in nuclear disarmament under Article 6 of the NPT. The deficiency to pursue this objective by the signatories, coupled with the expansion of nuclear weapon states from five in 1968 to nine as of 2021, indicates a global failure to address this continuing existential threat to humanity. A hazard that, until the coming into force of the TPNW, had not been illegal.

The lack of such prohibition was cited by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the “Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons”. The Court had noted that arms control agreements — until 1996 — did not constitute “comprehensive and universal conventional prohibition on the use, or the threat of use” of nuclear weapons. TPNW — as an instrument of international law — changes the status quo. Should another case related to the legality of nuclear weapons fall before the ICJ, those arguing for its legality will find their case resting on thinner ice.

While the treaty only applies to state parties, it marks an achievement on arms control norms in international affairs: The actors involved in the process have expanded from individuals and civil society to intergovernmental organisations. Thereby — through this evolution in the norm life cycle — handing activists a further authoritative benchmark to point to in their efforts surrounding nuclear weapons.

A symbol of progress for anti-nuclear struggles and an act of South-South cooperation

Next to this, the constitution of the agreement also provides nuclear disarmament movements, as concerned people around the world in general, with a symbol of progress in the matter. Not least, because its establishment largely is a success of activist fringes involved in the issue. This reflects the positive effects that these kinds of efforts can have. It points toward actions that could and should be undertaken in the future, if this existential threat to humanity is to be overcome.

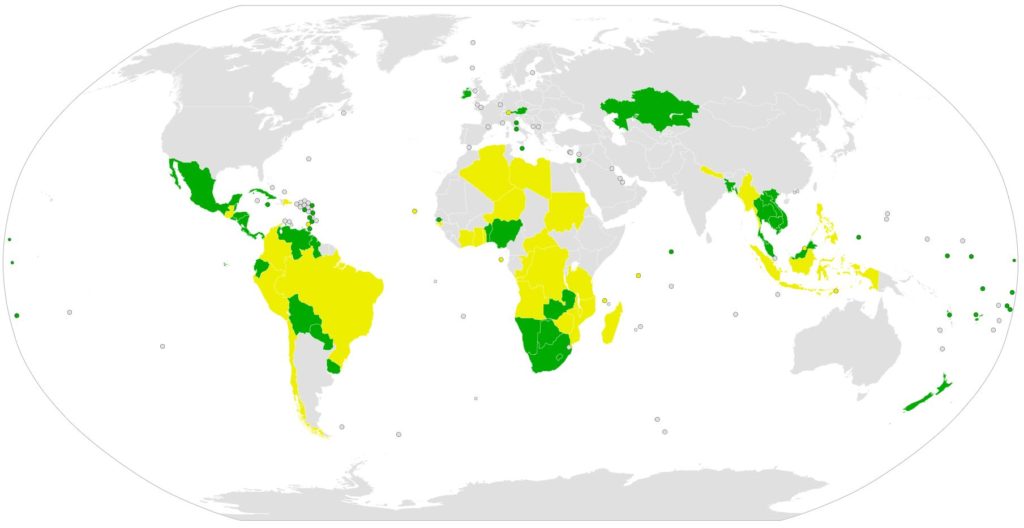

The treaty also constitutes an important act of cooperation and joint action among nations of the Global South. If one simply considers who are the signatories of the TPNW, this fact immediately becomes evident. Of all 193 UN member states “only” 84 signed the agreement — among them mostly countries from the developing world, which don’t themselves hold or produce nuclear weapons.

Crucially; all nine nuclear weapons states, as well as all NATO member states, neither signed nor even took part in the deliberations leading up to the accord — except the Netherlands, downvoting the adoption of the treaty at the July 2017 conference dedicated to the negotiation of the agreement. This division line between the signatories and non-signatories of the treaty runs (approximately) along the boundaries of Global North and South (see graphic below).

As in many other cases — whether they be economic or social or military etc. in nature — the same pattern persists. The South convenes and cooperates on an issue with work toward progressive ends in mind — most often balancing the scales of power and privilege between North and South — and the North abstains from participation and denies meaningful coverage in the outlets of its doctrinal systems; i.e. the media, academia.

The graphic shows the signers of the TPNW; divided into those who ratified the agreement (green) and those which have yet to do so (yellow). All countries coloured in grey have not signed the treaty. Source: Wikipedia

So, to take one case, which demonstrates this, which also happens to be directly linked to the issue of nuclear weapons; How many people in the West know of the hundreds (if not thousands) of civilians and veterans killed or severely injured by the effects of the US, France and Britain’s nuclear tests in Oceania? How often has one read in the Western press of the 500 time maximum of acceptable radiation that Tahiti, the most populated island in Polynesia, was exposed to during France’s nuclear tests there in the 1960-70s? How often did the words “literally been showered with plutonium for two days” as an investigator for the Polynesian government, Bruno Barillot noted, appeared in major European publications? This stands in stark contrast to the long held official position of the French government that their nuclear tests had always been clean. How many people know that out of 800 dossiers filed against the French government by victims of the test or their families, only 11 have received compensation thus far? Their voices — as the voices of the victims of the Global North in general are — largely go unheard.

Another case, which reflects the same pattern, occurred in February 1999, when two sets of significant economic talks were taking place simultaneously. One were the talks of the G-7 (seven wealthiest nations), which, as usual, received ample coverage in the western media. Another were those of the G-15 — now 18, then 17 countries from the so-called developing world, including in them economically quite substantial ones, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, India, Indonesia and Nigeria — countries which can’t just be dismissed from the world stage. The sets of talks between these nations received remarkably less attention in the western world; in some countries, like the United States or Great Britain, close to none (some in the BBC World Services and a couple of scattered sentences here and there aside).

In them, leaders from the Global South lamented the fact that the United States and Britain were unwilling to enter into dialogue with them on a number of issues. These included possible reforms to World Trade Organization rules, which might, for a change, not only benefit Northern countries, but also those of the South beyond the level which they are usually accustomed to; that of left-overs from the rich’s table.

The North’s main exponent and its faithful “lieutenant” (as a senior Kennedy adviser once characterised the US-British relationship) however remained silent on the occasion — as on so many others. And neither this, nor the plea to consider some moderate controls on foreign, mainly Western, investment were heard by political actors in the West or echoed by their counterparts in the media.

In opposition to this kind of irreverence, DiEM25, which has consistently denounced armed conflict and called for peaceful resolution of disputes, calls for — as a first step — the removal of all nuclear weapons from the European territory. We further denounce the encroachment of the arms industry into primary and secondary education — an important aspect which is often not considered. But schools should not be part of the normalisation of the next generation to war. We also remain concerned over the allowances provided to nations for their military emissions under the Paris Agreement — noting that the US military alone emits more than 140 countries combined.

Join us in our endeavour to further the disarmament of Europe.

Image source: Map of TPNW Treaty Participants on Wikipedia

This article was authored by Tom Stopford and Amir Kiyaei who are members of the Peace and International Policy DSC.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here