Greece, for years, has neglected ground-level activism. As we move into a period of greater authoritarianism, social conservativism, and ‘growth’ at all costs, this has to change

Since I moved away from Athens, boy do I miss it. Not the grime; not the pollution and the traffic, sure. But the spirit of the place. It’s like a scruffy old uncle, eccentric and bookish, whose stories make you feel alive.

And so last weekend, I found myself in that city for a day. The purpose of my visit wasn’t politics. But I was in the capital at a pivotal time in Greece’s modern democracy.

The country had just held a election. And the incumbent right-wing New Democracy (ND) party won… in a landslide. There will be a second vote on June 25, and barring a major upset/miracle, ND will likely tighten their grip on power.

There’s no glossing over it. Greece has swung decisively to the right.

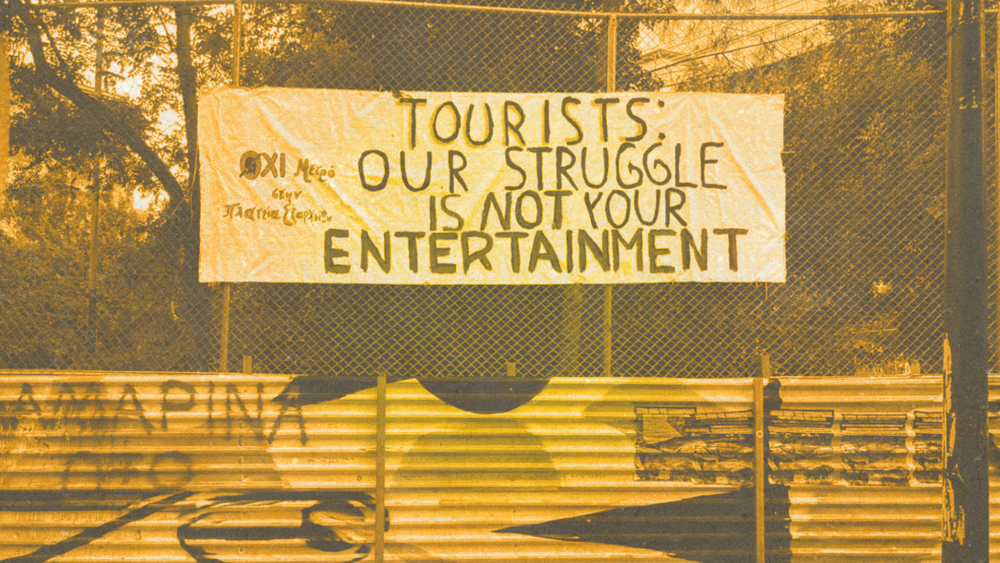

With this shift on my mind I wandered through Exarchia Square, the heart of the historic anarchist district, through the late afternoon shadows. For decades, the police rarely came here. But now, a hundred riot cops guarded a building site, a future metro station, bang in the middle of the plaza where a leafy playground once stood. Spray painted signs on the corrugated walls called meekly for the trees to remain intact, and warned tourists: “Our struggle is not your entertainment”.

The metro project was announced two years ago, as part of a drive to modernise (or gentrify) the capital. No-one knows when the station will be completed. “We’ll fight them all the way,” said the tired-looking woman in the bookshop, whose establishment lies ten metres from the fence.

I moved towards Syntagma and the parliament building, past closed shops and fraying campaign posters, and cut across the infamous walkway beside the National Library. Here the drug use, drug selling, drug everything was more open, more brazen than I’d remembered it, and I hurried through. Soon I was in Koukaki, my old neighborhood, now a haven for wealthy tourists with boutique hotels, juice bars, surly hipsters selling overpriced street food. A glimpse, perhaps, of what’s in store for Exarchia, too.

Greece’s deeper-rooted problems are less obvious to the casual visitor. But over the past year, a series of national crises has brought them into full relief, with the ND government firmly at the centre of each. Greek coastguards were filmed abandoning desperate migrant families at sea, in violation of international law and contradicting their own statements. The country’s intelligence agency, under the direct control of the prime minister, was caught monitoring the phones of Greek politicians and journalists. (Greece was slapped with the lowest press freedom rating in the EU by Reporters Without Borders, ranking behind Qatar, Thailand and Chad.)

And, of course, there was the train crash in northern Greece last February. It killed 57 people including many students. And was utterly avoidable – a tragic symptom of the corruption, graft and incompetence that has pervaded successive Greek governments for decades.

And yet. In these elections, Greek voters rewarded ND and its dynastic prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, with a stronger mandate. And rejected the leftist alternatives, decimating the leading opposition party Syriza in the process.

Plenty has been written about why this happened; that Greeks voted for stability over system change. That ND ran a disciplined campaign that resonated (always easier with a government-friendly press), while opposition parties — including MeRA25, whose parent organisation DiEM25 I work with – made pitches to the electorate that foundered. That Greeks lost their minds, got suckered, or became individualistic.

This summer will certainly be a long period of reflection for everyone involved in the leftist Greek opposition.

But for now, I can’t help thinking that the country’s shift to the right is also an opportunity. Because it sets the scene for a comeback of a force that has been absent for too long in Greece: grassroots activism.

Greece’s grassroots: long-untended, now un-represented

A few threads are coming together. And before you accuse me of wishful thinking or confirmation bias, hear me out.

First, active Greek citizens on the left no longer have representation at political level.

Some context. As I discovered as a grassroots organiser in Athens at the height of the debt crisis, Greeks are among the most politically aware, engaged and creative people I’ve met. There is cynicism, yes; collaboration issues, sure. But there’s no shortage of horsepower and talent.

From 2010 onwards, the austerity policies enforced by the country’s lenders and compliant Greek governments wore down society. There was no political force to temper these moves, as wages and pensions were slashed, taxes raised, and large parts of Greece’s assets privatised.

These injustices created a fertile environment for grassroots action. And in 2014, some friends and I did a study on this phenomenon. We found 415 informal groups across Greece, working in a variety of areas from health and education to the environment and human rights. These groups were stepping in where the state fell short, providing much-needed solidarity. And they were pushing back on the state’s excesses, opposing privatisations, blocking dangerous corporate projects, and holding the government to account with citizen media operations. They were creative, peaceful, and often remarkably innovative.

Yet in 2015, all that changed. The left-wing Syriza party came to power, confronted its international lenders, and soaked up the activist energies of the grassroots. Many groups had already folded into Syriza, and stopped their work; others simply fell into inactivity.

Events at this point in history are well documented. Syriza capitulated to Greece’s lenders, and became the enforcer of the austerity it had opposed. And Greek grassroots activism never really recovered. Even in 2019, when Syriza were voted out, grassroots Greece remained largely dormant. Today, there are spots of organised grassroots activity. But it’s piecemeal, and nothing like the blooming that preceded 2015.

There are many possible explanations: disillusionment, apathy, years-long crisis fatigue. But a dominant factor, I think, is this: Though many left-leaning Greeks stopped rooting for Syriza after the 2015 surrender, their aspirations were still broadly represented at the political level. As long as Syriza is a strong Greek political force, the calculation went, someone up there has my back. And so for the last eight years, there has been little impetus for grassroots organising.

All that changed a few weeks ago, with the last election. Syriza is now a shadow of its former self, with 20% of the vote, down from 31% in 2019. Other leftist parties with an activist base, including MeRA25, are still small. There’s no longer a vehicle in parliament to advance the interests of the grassroots.

Government over-reach sadly guaranteed

Second, there’s a strong likelihood that the need for grassroots action in Greece is about to shoot up. Because ND is inevitably going to over-reach.

Yes, the debt crisis is, at least in terms of perception, behind us. Yes, this iteration of ND is a slicker, better managed version of the party that brutalised the country in government for much of that period.

But ND’s clarity and message discipline in these recent campaigns, brought about by the electoral timeline and goal, will dissipate after the second election. And when the new ND government takes office, it’ll be drunk on its newly-acquired power. With many more variables and interests and patrons to manage than before. And due to the (likely) enormous mandate it will get from the public, with its most conservative tendencies unchecked.

All of this is a recipe for over-reach. For a government to take gambles, push forward policies that make a large segment of the population see red.

It’s hard to say now what form those injustices might take. It could be doubling down on evictions, water or healthcare privatisations. A new contested construction project. Or a policy shift that destroys livelihoods.

But whatever the shape of the over-reach, it may be precisely the motivator that grassroots Greece needs to wake up once again.

A chance for a reboot

Such a comeback could resemble the 2014 landscape of grassroots Greece. Or it could be something different entirely.

Certainly, the tools and know-how are out there as never before. There are tons of examples of best practice, from Serbia to Germany to the UK. Greek activists are more connected and better equipped than ever.

The only thing for sure is that the old resistance playbook no longer works. Marching with banners along the same route is ineffective, and too easily countered. Petitions alone are a blunt tool. Violence always undermines your objectives. Highlighting issues is insufficient.

* * *

Let me be clear. I’m not suggesting giving up on party politics. Making change happen requires both institutional work and ground-level activism.

But in Greece, it’s undeniable that for years we’ve neglected the latter and focused on the former. And as we move into a period of greater authoritarianism, social conservativism, and ‘growth’ at all costs, it’s time – more than ever – to address that balance.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here