The targeting of Russian culture and individuals reveals more than hypocrisy

“War is so unjust and ugly that all who wage it must try to stifle the voice of conscience within themselves,” wrote Leo Tolstoy in his diary in the winter of 1853.

Last week, 169 winters later, Netflix announced it was putting its TV adaptation of Tolstoy’s classic Anna Karenina on hold in the wake of Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine. Despite a life of principled pacifism, Tolstoy had made the unforgivable mistake of being Russian.

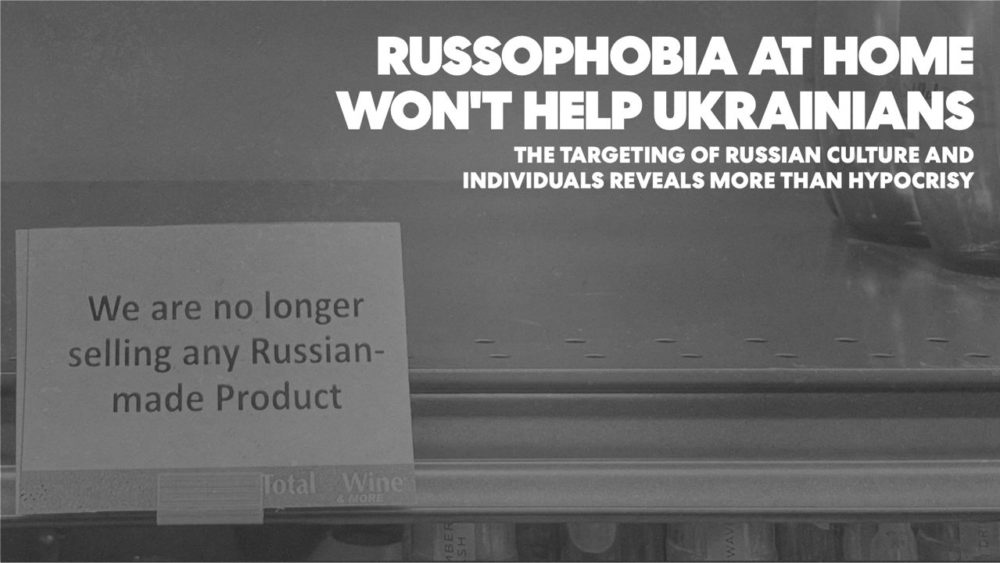

Other long-dead artists and intellectuals have been similarly punished. The Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra removed one of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s works from a program. A course on Fyodor Dostoyevsky was cancelled at the University of Milano-Bicocca (the school later backtracked). Most confusingly, a statue of the German Friedrich Engels became the centre of controversy in Manchester. Unfortunately, however, the Russophobia frenzy has reserved most of its ire to the living.

Russian films have been pulled from festivals. Eurovision banned Russian acts. Russian musicians have had their concerts cancelled, despite opposing the invasion. Even Russian cats have been told they’re no longer welcome in competitions.

Some of these measures have been justified by supposed ties between individuals and the Kremlin – but even then, reality is murkier than it appears at first. The Glasgow Film Festival explained their decision to ban two Russian films from being shown by pointing to the fact that they had received funding from the Russian Ministry of Culture. But other productions funded by public money, such as Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan, are deeply critical of Russian society and the Russian establishment. Leviathan was released in 2014 to general acclaim and received multiple awards in the Western festival circuit.

More disturbing than this, though, are the numerous reports of less-visible discrimination in Europe since the start of the war. People have been targeted on streets and in public transport, and children have been beaten and humiliated at school. A molotov cocktail was thrown through the entrance of a German-Russian school in Berlin.

Some elements in society seem to have picked up the message currently being sent by their institutions and decided to add a more straightforward twist to it. Largely condemned by commentators and the general public (when reported and acknowledged), these attacks are nevertheless the natural consequence of the climate being created. Once the threshold of discrimination has been crossed, it’s difficult to retrace one’s steps.

Xenophobia will not help stop the senseless loss of innocent lives in Ukraine. Just as we stand with the Ukrainian people in their fight for their land, we must speak out against these knee-jerk reactions, which represent the opposite of what the West claims to stand for. They do nothing but fuel the Kremlin’s propagandistic claims that the West is, at the end of the day, simply against all things Russian – a bunch of moralists who shake their heads at Russian society for their prejudices and supposed taste for authoritarianism, only to jump at the first opportunity to persecute people based on their nationality and cultural background, if the collective mood allows them to do so with impunity.

But the current wave of xenophobia reveals more than simple hypocrisy. The West, as the American scholar on Russia, Stephen Kotkin, recently argued, is not a place on the map, but “a series of institutions and values” which, in Kotkin’s view, includes the rule of law, democracy, respect for the individual, diversity and pluralism of opinion. By attacking people for the mere fact that they hold a Russian passport, taking measures that hit common Russians the hardest and banning Russian media, we reveal a worldview that is, ultimately, not defined by these values at all. It’s a worldview that’s shaped by conflict, but not a conflict in which we define allies and enemies according to ethics, class, or political struggles – instead, it’s one that separates sides along the lines of race, ethnicity and language.

There are names for such a worldview. Those in need of a refresher would do well to look them up.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here