Prologue

I’m walking along the side of the road, the only way through the village, back to my guest house in the south of Sri Lanka, when a moped driver smacks my bum while driving past. Before I can scream “arsehole”, he’s long gone.

While having a drunken conversation with a friend in a Berlin club, an unknown man takes hold of my breasts and arse. I wriggle awkwardly and move out of his grasp.

“Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters.”

-Rosa Luxemburg

One prominent face in particular has hovered over the debate surrounding #MeToo, offering us a mirror reflection of the whole. Since the publication of the article in the Le Monde the real roots of the problem can be espied shimmering in this rear-view mirror in the twilight. For Catherine Deneuve, at 74, is still a very beautiful woman.

The text, an open letter, was signed by around one hundred French women in response to #MeToo, a viral social media campaign that in turn became popular at the behest of the actress, Alyssa Milano. Originally, civil rights activist Tarana Burk started this movement called Me Too over ten years ago to highlight the extensive prevalence of sexual abuse and everyday sexual harassment. Since October last year, the hashtag #MeToo has brought together the stories of women with similar experiences: abuse, violence, assaults, unwanted flirtations, not having to say ‘no’: in other words, cultural norms, and always the question of who sets the norm. Full timelines for the compound of personal pronouns and particles.

In their letter, which appeared in one of France’s major newspapers, the women claim that the #MeToo debate has gone too far. It has created a “climate of denunciation”. They cannot, they say, identify with this feminism, a feminism that “beyond the denunciation of abuses of power, takes on the face of a hatred of men and sexuality.” They see themselves as the defenders of sexual freedom, fighters against a puritanism that ultimately plays into the hands of reactionary forces.

Many of the signatories are household names. They are writers, psychologists and actresses who, on average are not particularly young. A few days ago, Ms. Deneuve apologised to the victims of sexual violence. But she stands by her initial message. According to the German newspaper, TAZ (11.02.18), “Their intention, to defend sexual freedom against reactionary aspirations that put all intimacy under the cloak of moral political correctness and publicly denounce it, appears legitimate.” We could easily agree with this assertion, if we had already reached the degree of freedom that is theirs.

That this is very far from being the case is demonstrated by the ongoing protests of Polish men and women against attempts to further restrict abortion rights by their right-wing conservative government, modelling their move on the presidency of Donald Trump, which is deeply rooted in misogyny. It manifests itself in the struggle of the Kurds against the fascist rule of the so-called Islamic State, alongside the global strengthening of nationalist, anti-democratic forces. The fact that we simply have not reached this degree of freedom is also demonstrated by #MeToo – exactly the point that is not discussed in the letter to Le Monde.

Worldwide, commentators have waded in, in response to the response. The result is a simplified, for-or-against debate, an intellectual discourse that presupposes a concept of freedom and a concept of emancipation based on already existing privileges, which these French women evidently possess. We are all the same – chill out.

Like #MeToo for sexism, or #BlackLivesMatter is about racism, or #GrenfellTower for fatal structural failures – this is about policy that has proposed no alternatives for almost forty years. And what is the connection between the faces behind these hashtags? Socially created circumstance.

Anyone who has found themselves with an unwanted pregnancy, perhaps in their early twenties, will think differently about abortion: careerism, individualism, stigma, the right to life, early maternal feelings, pressure.

Those who know that success isn’t everything, don’t vote for the FDP. Those who know what the combination of sexuality, power and violence amounts to, don’t speak of lust.

But instead of responding with solidarity, something reductive typically happens with such debates. It develops into a form of primordial competition, an irridescent facet of global, deregulated, neoliberal capitalism. The philosopher and feminist Nancy Fraser criticises the dangerous liaison between feminism and neoliberalism. For her, it is important to break these up. So-called Second Wave Feminism, which strove for the expansion of individual autonomy, played into the hands of a new form of capitalism, through its ambivalence to development.

“The feminist turn to identity politics” writes Fraser, “dovetailed all too neatly with a rising neoliberalism that wanted nothing more than to repress all memory of social equality.” She continues, “we absolutised the critique of cultural sexism at precisely the moment when circumstances required redoubled attention to the critique of political economy.” Today it is one against the other, feminism against feminism, emancipation contre émancipation, woman against woman. We are not all the same.

While the French women are referring to a witch hunt, we are thinking of journalists in Turkish prisons. The comparison falls short and resembles an oxymoron. The activist, philosopher and feminist, Silvia Federici, who was associated with the Italian Autonomia Operaia, analyses the true witch hunt in “Caliban and the Witch“, and asks why the rise of capitalism demanded a genocidal attack on women?

Patriarchal rule, deeply interwoven with our economy, nation state organisation, and our way of seeing the world, with the categories we recognise, has an ugly face and is articulated in sexism.

Harvey Weinstein has become the archetypal hate figure, and Hollywood couldn’t have told it better. Among the murmur of voices, it is the rich and beautiful, the French women and the actresses in LA, those in the Western world, who speak in Le Monde Diplomatique and on other analogous and virtual newspaper platforms.

Others tweet a #MeToo about it, or keep silent, or both. And after it has been labelled as hysteria, the real, structural problem falls through the cracks.

Attempts to not perceive other women as competitors, whether in the working world, in love or in friendship, often encounter resistance. This becomes particularly clear at political events, often dominated by a male type of communication where every woman seems to have to fight for herself in order to be accepted as a fully-fledged political interlocutor. Where you have to pretend to be ‘one of the dudes´ in order to be recognized; check.

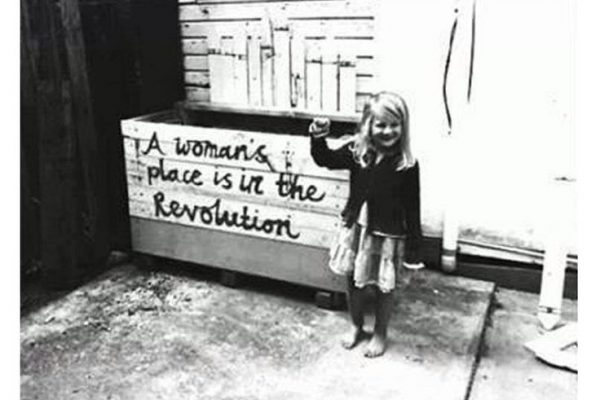

To finally break out of this spiral, it would be worth trying to free ourselves from this competitive thinking. Not an easy task, considering how deeply internalised such thinking is. If this ‘self-experiment’ fails, it is advisable to look two ways: back into that rearview mirror and forwards. Or to borrow again from Federici:

“It is through the day-to-day activities by means of which we produce our existence, that we can develop our capacity to cooperate and not only resist our dehumanization but learn to reconstruct the world as a space of nurturing, creativity, and care.” (Revolution at Point Zero).

Epilogue

I walk back to my guest house. Someone smiles while driving by.

In a Berlin club, I talk to a friend about lust and desire. I do not feel pressured. There is a difference.

Elisa is a member and volunteer of the DSC Munich.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here