“Miremos en silencio, aprendamos a oír, tal vez después, por fin, seamos capaces de comprender.”

— José Saramago, Our Word Is Our Weapon, 2002.

Recently, the Taskforce on Feminism, Diversity and Disabilities published two articles focusing on the increase of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) during COVID-19 and anti-trans violence that highlighted the lack of safety women and transwomen suffer but also that this crisis is not limited to a few countries or regions of the world.

The United Nations’ Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women: defines violence as “[acts] that result in, or are likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to [human beings], including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.”

European countries claim to have freedom but women and trans women are murdered every day because of violence by men — from partners, to neighbors, family members, workmates, and strangers. This is on top of the discrimination, exclusion, erasure, and psychological and sexual violence that is prevalent in patriarchal societies.

When it comes to addressing SGBV, governments have not given it the priority and effort they needs compared to the way other societal issues are systemically prioritised such as lending half a trillion euros to bail out the banks, spending billions of euros per year to keep occupying foreign countries, or closing and militarizing the borders in the name of “security”.

If nation-states are not able to guarantee basic rights for everyone, what are our options?

In Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state, a group of mostly indigenous people has been working for decades to create an alternative that offers other possibilities. This revolutionary group has understood from the very beginning that the success of their struggle was intimately tied to women’s liberation.

This feat is even more impressive given that Mexico not only has one of the highest femicide rates in the world, but is also a repressive State, and a society where patriarchy and colonialism play a significant role in women’s oppression. Even the way protests are covered by the media puts more focus on the protection of property than on human suffering, as was the case when feminists took over the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) offices in Mexico City, demanding the CNDH to defend women’s rights and provide assistance to survivors. The fact that the offices were converted into a women’s shelter where they also offered legal counsel was mostly ignored.

A Different Kind of Revolution

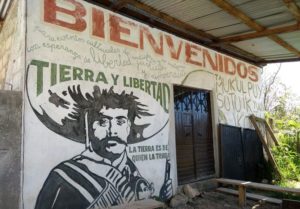

Photo: Mural of Emiliano Zapata by Road2Help.

This revolutionary group goes by the name of Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation), whose members and supporters alike are typically referred to as Zapatistas. From their inception, the Zapatistas understood that they could only achieve freedom if everyone became free, and that included being free of violence. With this in mind, they collectively agreed that women’s liberation needed to be one of their core tenets before rising up in arms and published their revolutionary women’s law, establishing a leadership that is half composed of indigenous women.

“It is clear to us that transformations must not focus only on material conditions. That’s why for us there is no hierarchy of spheres; we do not claim that the fight for land has priority over the gender struggle, nor that the gender struggle is more important than the fight to recognize and respect difference[s].

Instead, we think that all types of emphasis are necessary and that we must be humble and recognize that currently there is no organization or movement that can boast about covering all aspects of the antisystemic—that is, anticapitalist—struggle.

This recognition is the basis for our Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle. It sets out by recognizing and accepting the breadth of our dream and the narrowness of our strength.”

— Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, 2008 speech recorded in The Zapatistas’ Dignified Rage, 2018.

The Zapatista men took these laws seriously and obeyed them in solidarity with the women, including giving up alcohol — which was forbidden by the revolutionary women’s law as its abuse usually translated into domestic violence. Now, decades later, the Zapatista women are proud of living without fear of being killed in their territories. Florinda, a 15 year old Zapatista, explained during the second international gathering of Women who struggle (an event only for women organized by Zapatista women where “no men are allowed, even if they are good men or normal men or whatever men” that focused on violence against women):

“In the Caracoles, there aren’t women who are beaten by their husbands, nor murdered, because, among us women, we support each other, and also; drinking alcohol is prohibited… we also have the same rights as men have.” (in Spanish).

However, this achievement did not happen quickly nor easily, as Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano recalls in “The Vision of the Vanquished”. The Zapatistas are also aware that no matter how much progress they have achieved, there is always more that needs to be done. They start by admitting not to have all the answers and asking questions first, as they did a couple of years ago when they posed these questions to a group of scientists from 11 countries:

“What do you think about the fact that they use us [women] as publicity for their propaganda and their transport of drugs, and as objects to satisfy their sexual needs? That they prostitute us to sell articles to make money?”

So, how can a group composed mostly of historically oppressed and economically exploited people, under constant attacks by the government and paramilitary groups, be able to achieve the seemingly impossible, while governments with resources, funding, and facilities cannot fulfill their responsibility of protecting the safety of their citizens?

We need to ask ourselves what is causing these acts of violence and domination, who is committing these actions, and why they keep happening

It should not only be our States and political leaders who are under scrutiny. We should also be critical of ourselves; after all, if laws were enough there would not be any crimes.

For instance, patriarchal culture is mostly focused on survivors, e.g. we tell our daughters to be careful, but we do not teach our sons to not harass, assault, nor rape. The rare cases when society goes against the perpetrators, it does so on an individual level instead of recognizing the systemic and systematic issues taking place. An example of being critical of our society can start through this thought experiment by Natalia Zeller asking what are the answers if we asked men what they would do if there were no women for one day; and compare that to the answers given by women. Why are we, as a society, not outraged by how unsafe women feel walking alone in the streets? And more importantly, what are the individual and collective actions that we must make to eradicate the violence that disproportionately affects women?

If there is something we can learn from the Zapatistas, it is that these issues cannot be resolved through policies and laws alone. The Women’s Revolutionary Laws are a success not because they are laws, but because the communities agreed that those were basic rights for everyone and are followed without coercion, using self-organization, mediation and restorative justice instead of a punitive approach. If this can be done in Chiapas, Mexico, what is preventing us from doing it everywhere?

We should not be discouraged from searching for the answers to these questions, but be motivated by the opportunity to do so and to envision a safer society for all. In doing so, remember to actively involve everyone, especially those who are the most affected by our decisions.

We demand femicide to be internationally recognized as a crime against humanity. Through this, gaps in justice and criminal systems can slowly be addressed. In addition, we also invite everyone to sign this petition by the Kurdish Women’s Movement in Europe that draws attention to the femicidal policies by the AKP Party in Turkey.

The Gender 1 DSC at DiEM25 will be launching a campaign addressing SGBV in 2021 as part of our ongoing work to raise awareness on the issue. Contribute to shaping our campaign, or find ways we can support each other by contacting the Taskforce of feminism, diversity and disabilities: fdd@diem25.org.

Featured Photo: A picture of the international gathering for women organized by the EZLN showing signs that read “welcome women of the world” and “men are not allowed”.

Photo Sources: Road2Help.

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25's actions? Sign up here